Contemporary BioArt, fueled by gene editing (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9), synthetic biology,

microbial manipulation, data science, and AI algorithms, transforms the laboratory into a

creative arena (Reichle, 2009; Mitchell, 2010). Liberated from static media constraints, art

now revolves around dynamic, evolving life processes. Artworks emerge not solely from

human creators but through an interplay of microbes, algorithms, environments, and

audiences. This shift reshapes aesthetic logic and incites profound debates in philosophical,

ethical, social, and ecological dimensions.

Philosophical and Theoretical Background: Materializing Posthumanism and Biopolitics

Posthumanist theory (Donna Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto, 1991; Rosi Braidotti, The

Posthuman, 2013) urges us to reexamine life and value in multispecies, multi-actor networks,

rejecting human exceptionalism. In BioArt, gene editing and cell cultivation place nonhuman

life forms (fungi, microbes) and technological systems (sensors, algorithms) into the creative

process. Abstract posthumanist ideals thus materialize: viewers must consider fungal growth,

microbial metabolism, and algorithmic decisions, rather than focusing solely on human intent.

Meanwhile, biopolitics (Foucault; Agamben) addresses life’s governance and distribution.

BioArt’s manipulation of genetic resources and microbial ecologies provides a sensory entry

point into these power dynamics. Exhibitions can present genetic patent clauses,

environmental movement cases, and expert interviews, transforming “biopolitics” from a

scholarly term into a tangible problem scenario. Audiences recognize that beyond artistic

novelty lie economic and political forces shaping life itself.

Case Analysis: From Individual Spectacle to Systemic Perspectives

Early bio-artists often carried the aura of mad scientists, with many of their works delivering

a powerful and provocative impact. Early BioArt milestones like Eduardo Kac’s GFP Bunny

(2000), which introduced a fluorescent gene into a rabbit, triggered public fascination an

anxiety over biotech’s aesthetic and moral stakes. Without deeper interpretation, such works

risk trivialization as mere spectacle. By contextualizing their techno-social backgrounds,

audiences perceive not just novel visuals but prompts to question genetic authority and

public understanding.

Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr are pioneers of bio-art, they established Tissue Culture & Art

(TC&A) in 1996, renowned for their bold explorations of the definition and control of life.

Their early work, Semi-Living Worry Dolls, used tissue culture techniques to “grow” semi-living dolls composed of living cells and biological scaffolds, blurring the boundaries between

life and non-life. The piece, both visually striking and deeply unsettling, sparked intense

debates about ethics, the commodification of life, and humanity’s power to manipulate

nature, cementing its place as a landmark in the intersection of science and art.

Recent BioArt endeavors embrace more systemic thinking. Some artists employ GANs and

evolutionary algorithms to model microbial communities, adjusting conditions via

environmental sensor data. This surpasses isolated ethical shocks, highlighting information

asymmetry, resource inequities, and potential regulatory voids. Instead of a single-level moral

dilemma, viewers confront a vast socio-ecological framework.

Anna Dumitriu is an internationally renowned bio-artist known for integrating cutting-edge

scientific technologies with artistic expression. Her work delves into fields such

microbiology, antibiotic resistance, synthetic biology, gene editing (including CRISPR), and

artificial intelligence, often in collaboration with scientists to transform the latest research

into works that are both academic and artistic. Her notable works include The Bacterial

Sublime and Make Do and Mend, which explore the microscopic world of bacterial

communities and the history of antibiotic resistance, respectively. In Engineered Antibody,

she presents the artistic potential of gene editing, while her AI-based projects analyze

biological data to investigate the boundaries between nature and the artificial.

Beyond the West, other cultural contexts reinforce BioArt’s global dimension. Mexican artist

Gilberto Esparza’s Plantas Nómadas couples microbial fuel cells and plants to address

environmental pollution and resource control. Chinese artist Zheng Bo, though not always

using gene editing, integrates plant ecologies into artistic inquiry, linking human-nature

relations to subtle political and cultural narratives. These cases show that BioArt can engage

agricultural traditions, local biodiversity, and communal knowledge, demonstrating that life

politics and resource challenges transcend Western settings.

Controversies and Multiple Perspectives: Balancing Knowledge, Property, and Public Attitudes

BioArt’s controversies span multiple levels:

- Scientists fear insufficient experimental rigor and potential public misunderstanding. Artists

seek to democratize knowledge production, challenging scientific hegemony. Exhibitions

that present scientific critiques alongside artistic visions highlight that knowledge

frameworks are not neutral. - Gene patents and bioproperty raise moral and legal dilemmas: is artistic use legitimate and

ethical? Might audiences be nudged toward irrational biotech admiration? By juxtaposing

legal texts, industry data, and artist testimonies, viewers gauge how art subtly influences

public sentiment. - Environmental groups protesting an exhibition for implying bioresource misuse exemplify art

as a catalyst of public concern. Instead of neutral objects, artworks become arenas of

contested values. This reveals how BioArt spotlights moral boundaries and engenders

societal reflection on technological incursions into life.

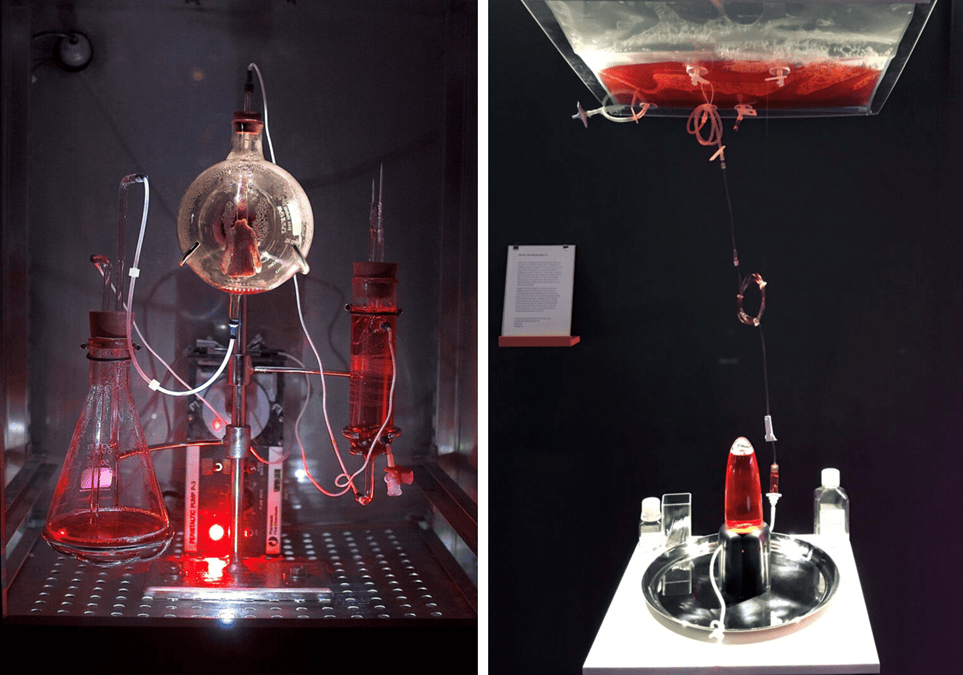

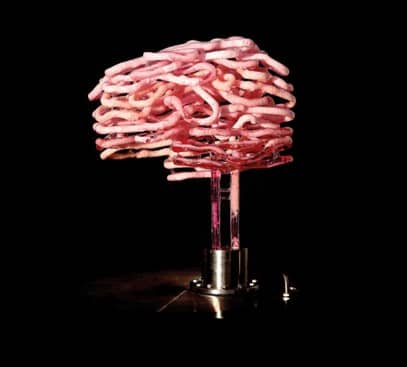

Right: Nutrient Bug1.0: Stir Fly, in collaboration with Robert Foster, 2016. The Tissue Culture & Art (Oron Catts & Ionat Zurr)

Ecological Dimensions and Capitalist Logic: Sensory Bridges to Grand Narratives

Transgenic plants, fungal installations, and microbial ecosystems metaphorize global

ecological crises and capitalist monopolies over genetic resources. Curators can use data

visualization and storytelling, turning policy debates into sensory scenes. Observing microbial

imbalances, viewers sense how capital molds environments. Such experiential translation is

deliberate, connecting personal encounter with larger ecological-political discourses.

Exhibition Mechanisms, Education, and Public Participation: From Passive Reception to Collaborative Insight

BioArt exhibitions demand careful technical arrangements and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Microscopic observation points, data interfaces, and workshops let audiences attempt

microbial cultivation or data analysis. Participation enhances scientific and ethical literacy

turning exhibitions into collective inquiry forums. Instead of passive consumption, viewers

become knowledge co-producers, enriching public debate on gene editing, biosafety, and

environmental governance.

intervention – Photo by Ziyin ZHANG

Redefining Subjectivity and Creative Logic: A Bio-Tech-Human Nexus

In BioArt, outcomes emerge from microbial proliferation, environmental fluctuations

algorithmic judgments, and audience input—not solely from the artist’s will. This distributed

subjectivity enacts posthumanist ideals, positioning artworks as relational nodes rather than

isolated objects. Recognizing this collaborative ecosystem offers a cultural reference fo

future art-tech experiments that acknowledge nonhuman agencies.

glucose, which was used to cultivate human brain cells in a glass reactor.

Future Directions and Practical Strategies: Ecological Accountability and Governance Structures

As CRISPR and gene drive technologies mature, BioArt could affect ecosystems on a grand

scale, risking irreversible environmental impacts. Focus should shift from technical details to

social and ecological accountability. Involving environmental NGOs, policymakers, and

scientists in exhibition dialogues exposes audiences to multiple stances and impending

responsibilities. International agreements, professional guidelines, and public consultations

ensure that innovation remains transparent and answerable.

Public education is crucial. Establishing BioArt public labs—offering free workshops and

immersive sessions—lets citizens grasp basic biotech principles, enabling them to critically

assess bioresource patents, GMO crops, and environmental policies. Such initiatives turn art

venues into educational platforms for the biotech era, fortifying public judgment and

empowerment.

Frontier Topics and Cross-Sectoral Expansion: Diverse Information and Immersion

CRISPR-based genomic refinements, GAN-driven microbial simulations, blockchain-mediated gene usage tracking, and VR/AR immersions reflect BioArt’s expanding frontiers. Curators can provide supplementary readings, thematic symposia, and VR installations, offering multiple information sources. In VR environments, visitors “enter” cellular worlds adjust microbial growth conditions, and observe algorithmic forecasts, rendering abstract concepts tangible and experiential.

Indonesian collective Lifepatch integrates DIY bioexperimentation with local ecological and

community practices. Their approach merges bioartistic inquiry with agricultural traditions

and environmental challenges, exemplifying how BioArt, in diverse cultural contexts,

reinterprets life politics and resource control beyond Western paradigms.

Humility, Responsibility, and Value Reassessment: Guarding Against Techno-Utopianism

While embracing the synergy of art and technology, one must resist naive techno-utopian

visions. Emphasizing humility, introspection, and responsibility is essential. When life is

artistic material, innovation carries risks and reorders power. Incorporating philosophical,

ethical, and social science voices in exhibitions and critical essays prevents art from

becoming a tool for capital-driven spectacle or unchecked tech worship. Balanced vigilance

ensures that beneath aesthetic allure lies awareness and critical thought.

Conclusion and Outlook: Revisiting Core Threads and Future Inspirations

BioArt’s significance lies in posing deeper, more complex questions rather than offer

simplistic resolutions.

By comparing early and recent cases, highlighting multifaceted controversies, and proposing

concrete measures, the dynamic evolution of BioArt’s knowledge-value network comes into

focus. Immersive technologies, public labs, and multi-viewpoint exhibition sections empower

audiences to form independent judgments amid conflicting narratives.

BioArt goes beyond merely applauding or condemning technology, serving instead as a public

forum where life, technology, and aesthetics intersect. With clarified thematic threads, more

coherent case analyses, and tangible action recommendations, BioArt exhibitions transcend

spectacle, evolving into laboratories of societal inquiry, challenging our understanding of

existence, responsibility, and future destinies in an era of perpetual flux.

Ziyin Zhang