1979, Téhéran.

La révolution ébranle le pays et sa population. Cyrus Farzadi, 25 ans, travaille au Musée d’Art contemporain de la ville. Musée développé et construit par le cousin de l’impératrice, Kamran Diba. Ce lieu marqueur d’un régime passé, d’une vie luxueuse, d’une ouverture occidentale est menacé suite à la prise de pouvoir des mollahs et de l’Ayatollah Khomeiny.

Cyrus réussira-t-il à sauver les toiles des maitres occidentaux face à l’obscurantisme des mollahs ? Le Téhéran du Chah peut-il encore exister à travers ces monuments malgré la montée du régime islamique ?

Introduction :

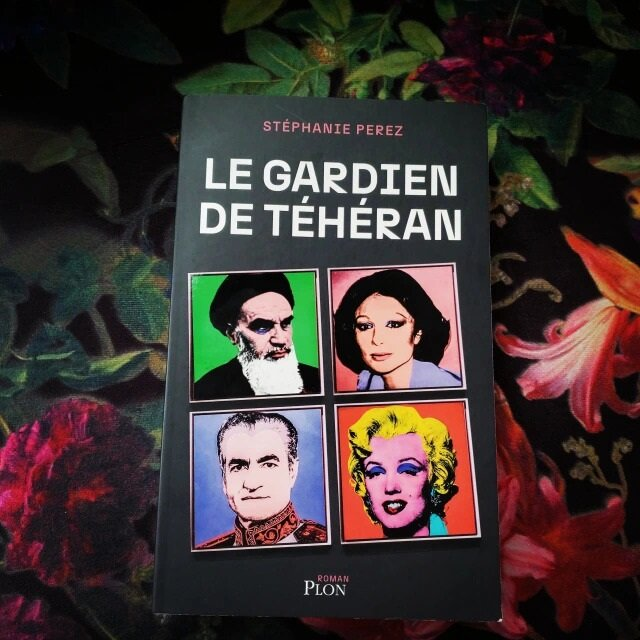

Stéphanie Perez est une journaliste grand reporter chargée de l’internationale à France Télévisions pour les journaux de France 2 et France 3 depuis plus de vingt-cinq ans maintenant. Elle s’est rendue à plusieurs reprises au Proche-Orient, afin de couvrir notamment les conflits en Syrie et en Irak et plus tard en Ukraine. Elle a remporté en 2018 le prix Bayeux des Lycéens et en 2020 le Laurier du Grand Reporter.

Le Gardien de Téhéran, son premier roman, s’inspire d’une histoire vraie. Stéphanie Perez introduit ce livre en justifiant le choix du roman et non du documentaire pour la préservation de l’identité et de la vie des personnes qui ont créé les personnages du livre et ainsi de relater la Révolution Iranienne dans les années 1970. Elle souligne également la complexité de l’Iran et la fragilité de la parole et de la mémoire de ces personnes qui ont contribué à l’enrichissement et à la préservation du Musée d’Art Contemporain de Téhéran.

L’Iran des années 1970 :

Cyrus Farzadi vit dans les quartiers populaires à l’Ouest de Téhéran dans un petit appartement avec sa mère Farideh. Elle est coutière, travaille pour les occidentaux vivant à Téhéran, pour cette classe élitiste qui fleurte avec l’extravagance, les soirées mondaines et la frivolité qu’offre le règne des Pahlavi. Elle raccorde les robes de soirées de ces jeunes dames parfois tard le soir. Cyrus est un grand timide, discret et contentieux. Il travaille comme livreur, jusqu’à sa rencontre avec Donna Stein au musée d’Art Contemporain, où il livre de la moquette.

Le musée d’art contemporain de Téhéran fait partie des nombreux bâtiments en construction. Farah Pahlavi, aussi appelée « L’impératrice des Arts » souhaite donner une nouvelle vision de l’occident. Elle a chargé son cousin Kamran Dabi de développer la collection de ce nouveau musée et de s’entourer des meilleurs experts. Il travaille en étroite collaboration avec Donna Stein, une américaine qui connait bien le monde de l’Art contemporain. Ses connections avec New York et les grandes maisons de ventes anglaises facilitent l’accès à ces œuvres et ce marché. La crise pétrolière de 1976 a mis les marchés occidentaux dans de mauvais draps, alors que l’Iran croule sur l’or. Le musée acquière pour des sommes minimes des Warhol, Hockney, Bacon, Renoir, Pissarro…pour ne citer qu’eux. C’est l’argent du pétrole qui permet au marché de l’art d’atteindre des sommets impensables pour les occidentaux.

Cyrus découvre un monde auquel il se forme grâce aux œuvres qu’il transporte mais aussi grâce aux rencontres qu’il fait. Lauren, sa jeune collègue anglo-iranienne s’occupe de la restauration des tableaux et lui transmet tout son savoir sur l’histoire des œuvres qu’elle travaille. Elle aide également à la traduction du catalogue. Mona Tavoli, son mari et sa fille Pouran aideront Cyrus à authentifier les œuvres du musée.

Le 14 octobre 1977, lorsque le musée fait sa grande cérémonie d’inauguration les Pahlavi sont présents ainsi que de nombreux experts occidentaux, et d’autres personnalités comme Grace de Monaco, le futur roi d’Espagne, des magnats du pétrole, des stars de la jet-set….

Les célèbres critiques d’Art français Georges Boudaille et André Fermigier ne comprennent pas et ne prennent pas au sérieux ce nouvel intérêts de l’Iran pour l’art « occidental ». Toutefois, lors de l’inauguration ils sont plus qu’impressionnés : comment l’Iran a-t-il pu se procurer de tel chef d’œuvre ?

Merci l’or noire !

La Révolution :

Depuis le mariage de Mohammad Reza Pahlavi et Farah Diba en 1967, la société s’est davantage divisée : une classe élitiste qui profite de cet américanisation/occidentalisation de la société iranienne qui vit de fêtes, de modernité et d’extravagance. Et l’autre classe, populaire, qui vit tant bien que mal dans une société qui l’omet et ne répond pas à ses attentes.

Pourquoi le Chah souhaite tant offrir à ces occidentaux quand son propre peuple meurt de faim ?

La construction de ces multiples musées et ces acquisitions d’art occidentaux interrogent la population. « Quel est le sens de l’art contemporain ? Qu’apporte-t-il au spectateur ? C’est une vaste question qui fait débat, même en Occident, mais pour Ali [l’oncle de Cyrus,] elle est devenue politique et religieuse. »

Le ras le bol général des classes inférieures ainsi que la négligence et l’indifférence du Chah et de l’Impératrice à leur égard accentue le bouillonnement révolutionnaire. Sans compté sur la censure et La Savak, la police secrète du Chah, qui grâce à une loi de 1957 peut « arrêter toute personne soupçonnée de ‘complot contraire à l’ordre public’ ».

Azadeh, la voisine et amie de Cyrus, étudiante en droit à l’université de Téhéran, connaitra La Savak. Cette jeune femme volubile a soif de vengeance et de liberté du peuple, rêve d’un monde plus égalitaire… Les récits les plus affreux sont répandus dans le pays quant au sort des prisonniers… Mais celui d’Azadeh est unique et si représentatif de cette société biface. Les signes protestataires du régime du Chah sont de plus en plus présents, notamment le port du hijab, signe contestataire du model américain apporté par les Pahlavi.

Dans cette atmosphère lourde et pesante, le Chah est renversé. Sa femme et lui s’exilent dans divers pays, abandonnant leur vie, leur palais et le Musée d’art contemporain avec tous ces chef d’œuvres derrière eux. Khomeiny, ses mollahs et le reste de la population prennent possession des rues, des bâtiments. Les révolutionnaires détruisent tous ce qui est impie à leur yeux, tout ce qui ne représente pas l’Iran, le Vrai. « […] la petite salle de théâtre expérimental au coin de la rue » a été détruite ainsi que les « cinémas qui projetaient des films américains » et toutes autres infrastructures qui rappellent « la volonté d’ouverture vers l’étranger, la modernité, l’ailleurs » des Pahlavi.

L’Iran d’aujourd’hui :

Cette révolution civile et religieuse aura fait basculer à jamais le pays, ses habitants, ses habitudes et ses pensées dans une nouvelle ère.

En 2016, « La prestigieuse collection de l’impératrice Farah Pahlavi est estimée par les plus grands experts mondiaux à près de 3 milliards de dollars ».

Le musée d’Art Contemporain de Téhéran existe toujours. Ces chefs d’œuvres voient la lumière du jour en fonction du directeur du Musée : tantôt ouvert, tantôt fermé à tout art contemporain occidentaux.

Le gardien de Téhéran, Stéphanie Perez – Sophie Juffet

1979, Tehran.

The revolution shakes the country and its people. Cyrus Farzadi, 25 years old, works at the Contemporary Art Museum in the city. The museum, developed and built by the Empress’s cousin, Kamran Diba, represents a marker of a past regime, a life of luxury, and a western openness. It is now threatened by the rise of the mullahs and Ayatollah Khomeini’s seizure of power.

Will Cyrus manage to save the paintings of western masters from the obscurantism of the mullahs? Can the Tehran of the Shah still exist through these monuments, despite the rise of the Islamic regime?

Introduction:

Stéphanie Perez is an investigative journalist responsible for international affairs at France Télévisions, covering the news for France 2 and France 3 for over twenty-five years. She has travelled multiple times to the Middle East, covering the conflicts in Syria and Iraq, and later in Ukraine. In 2018, she won the Bayeux Award for Young People’s Journalism and in 2020, the Laurier Award for Grand Reporter.

Le Gardien de Téhéran (The Guardian of Tehran), her debut novel, is inspired by a true story. Stéphanie Perez introduces the book by justifying her choice to write a novel rather than a documentary in order to preserve the identity and lives of those who created the characters in the book, and thus to recount the Iranian Revolution of the 1970s. She also highlights the complexity of Iran and the fragility of the voices and memories of those who contributed to the enrichment and preservation of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

Iran in the 1970s:

Cyrus Farzadi lives in a working-class district in the West of Tehran in a small apartment with his mother, Farideh. She is a seamstress, working for the westerners living in Tehran, for the elitist class that flirts with extravagance, high-society parties, and the frivolity offered by the reign of the Pahlavi. She often alters evening gowns for these young women, sometimes late into the night. Cyrus is a shy, discreet, and somewhat contentious young man. He works as a deliveryman until he meets Donna Stein at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, where he is delivering carpet.

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art is part of the many buildings under construction. Farah Pahlavi, also known as « The Empress of the Arts« , wants to offer a new vision of the West. She has tasked her cousin Kamran Diba with developing the collection for this new museum and surrounding himself with the best experts. He works closely with Donna Stein, an American who knows the world of contemporary art well. Her connections with New York and major English auction houses facilitate access to these artworks and this market. The 1976 oil crisis left western markets in a bad position, while Iran was awash in gold. The museum acquires works by Warhol, Hockney, Bacon, Renoir, Pissarro… for minimal sums, just to name a few. It is the oil money that allows the art market to reach unimaginable heights for the West.

Cyrus discovers a world to which he is introduced not only through the artworks he transports but also through the encounters he makes. Lauren, his young Anglo-Iranian colleague, is in charge of restoring the paintings and shares all her knowledge with him about the history of the works she works on. She also helps with the translation of the catalogue. Mona Tavoli, her husband, and their daughter Pouran will help Cyrus authenticate the museum’s artworks.

On October 14, 1977, when the museum held its grand inauguration ceremony, the Pahlavi were present, along with many western experts and other personalities such as Grace of Monaco, the future King of Spain, oil magnates, jet-set stars…

The famous French art critics Georges Boudaille and André Fermigier could not understand and did not take seriously Iran’s newfound interest in « western » art. However, during the inauguration, they were more than impressed: How could Iran have acquired such masterpieces?

Thank you, black gold!

The Revolution:

Since the marriage of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Farah Diba in 1967, society has become even more divided: an elitist class benefiting from the Westernisation of Iranian society, living in luxury, modernity, and extravagance, and another, popular class, struggling to survive in a society that ignores it and does not meet its expectations.

Why does the Shah wish to offer so much to these westerners when his own people are starving?

The construction of these numerous museums and acquisitions of western art raise questions among the population. “What is the meaning of contemporary art? What does it offer to the viewer? This is a vast question that sparks debate, even in the West, but for Ali [Cyrus’s uncle], it has become political and religious.”

The general frustration of the lower classes, as well as the neglect and indifference of the Shah and Empress toward them, amplifies the revolutionary stirrings. Not to mention the censorship and the Savak, the Shah’s secret police, which, thanks to a 1957 law, can “arrest anyone suspected of ‘plotting against public order’.”

Azadeh, Cyrus’s neighbour and friend, a law student at Tehran University, will encounter the Savak. This outspoken young woman is thirsting for vengeance and freedom for the people, dreaming of a more egalitarian world… The most horrific stories are spread across the country regarding the fate of prisoners… But Azadeh’s story is unique and so representative of this dual-faced society. The protest signs against the Shah’s regime are increasingly evident, especially the wearing of the hijab, a protest against the American model introduced by the Pahlavi.

In this heavy and oppressive atmosphere, the Shah is overthrown. He and his wife go into exile in various countries, abandoning their life, their palace, and the Contemporary Art Museum with all its masterpieces behind them. Khomeini, his mullahs, and the rest of the population take possession of the streets and buildings. The revolutionaries destroy everything that is deemed impious in their eyes, everything that does not represent Iran, the True Iran. “[…] the small experimental theatre at the street corner” was destroyed, as well as “the cinemas that showed American films”, and any other infrastructure that reminded them of “the desire for openness to the outside world, modernity, and the otherness” of the Pahlavi.

Iran Today:

This civil and religious revolution has forever transformed the country, its people, their customs, and their ways of thinking, ushering in a new era.

In 2016, « The prestigious collection of Empress Farah Pahlavi was valued by the world’s top experts at nearly 3 billion dollars. »

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art still exists. These masterpieces come to light depending on the museum director: sometimes open, sometimes closed to all western contemporary art.