Monuments across continents

Monumental architecture has an undeniable power to captivate us. Whether it’s the towering spires of a gothic cathedral or the symmetrical elegance of the Taj Mahal, these awe-inspiring structures leave an indelible imprint on the cultural landscape. Across different cultures and time periods, monumental buildings have become more than just functional spaces; they are expressions of human creativity, cultural identity, and spiritual devotion. But despite their geographical and temporal distances, why do we find so many shared characteristics in these iconic monuments? What do these structures reveal about our common humanity?

Architecture as Art: Creative Masterpieces Across Continents

Monuments are not merely functional; they are expressions of human artistry/creativity and physical embodiment of artistic vision. From the intricate details of the Taj Mahal to the grandeur of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, these structures go beyond their utilitarian purposes to become timeless works of art.

Take, for instance, the Pyramids of Giza in Egypt, which combine geometric precision and monumental grandeur, serving as both architectural feats and artistic triumphs of ancient Egyptian civilization. These buildings are cultural touchstones, each stone laid with deep symbolism and thought, serving as more than just shelter or space, but as vessels of identity, culture, and history.

These structures have artistic significance as much as cultural and spiritual value, becoming symbols of both the empires that built them and the civilizations they impacted. The cathedrals of Europe, such as Notre-Dame in Paris and St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, represent the intersection of art, religion, and power, where architecture itself serves as a medium for spiritual expression.

Yet, what is often hidden in the story of these monumental creations is the role of colonialism in the exchange of architectural knowledge. While colonial powers exported their architectural styles to far-flung corners of the world, they also absorbed and appropriated the designs and ideas of the lands they occupied. For instance, Mughal architectural elements from India, such as the minarets and arches of the Taj Mahal, can be seen echoed in British colonial buildings. The cross-pollination of ideas was a product of colonial exchanges, though often this history is obscured by elites who rewrite the narratives of these monuments to favor a singular, dominant cultural story.

The Artist’s Vision: Personal and Cultural Symbolism

One of the most fascinating aspects of monumental architecture is the personal and cultural significance embedded in each structure. Architects, builders, and craftsmen have long infused monumental structures with personal and cultural meanings, making each building unique. Whether designed by a single architect or built by thousands, these monuments often reflect a fusion of individual vision and collective cultural values. The Basilica of Saint Nicholas in Nantes, France, for example, combines intricate Baroque details with religious symbolism to evoke both devotion and grandeur. Similarly, the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City demonstrates how art and architecture can merge to create an immersive spiritual experience, where Michelangelo’s frescoes transcend mere decoration to convey religious narratives.

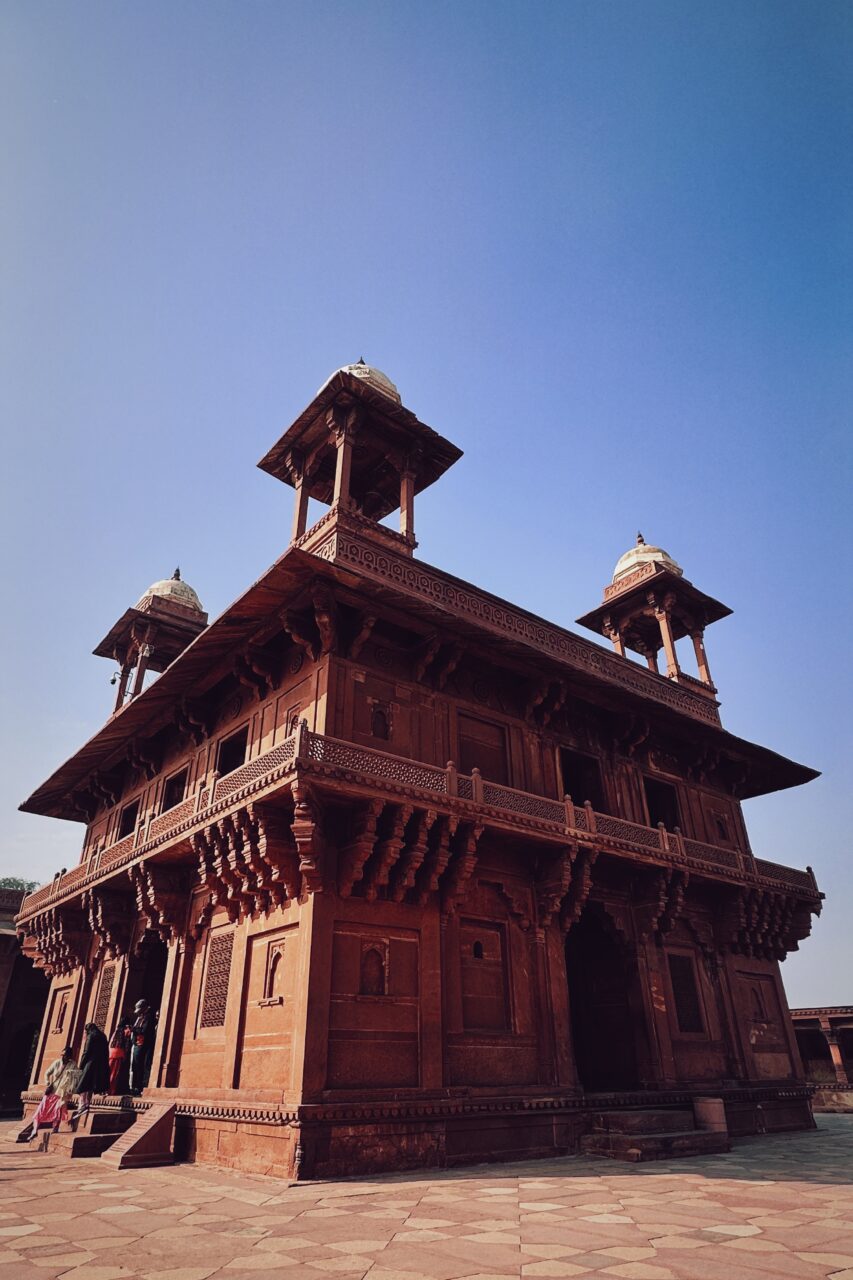

Relatedly, the Taj Mahal stands as a testament to Emperor Shah Jahan’s love for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, immortalizing their bond in white marble. In the case of the Fatehpur Sikri in India, we see the grandeur of Mughal architecture blended with Islamic and Hindu elements, illustrating the cultural convergence that took place under the reign of Emperor Akbar. Through intricate carvings and expansive courtyards, these monuments become a canvas for a diverse spiritual narrative that transcends religious boundaries.

These monuments also stand as testaments to the ingenuity of their creators. The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, designed by Frank Gehry, challenges traditional ideas of form and space, creating an architectural masterpiece that reflects the artist’s unique perspective. Likewise, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, a modern marvel, symbolizes both innovation and the desire for a lasting legacy, rising to unprecedented heights and reshaping the skyline of the city.

These structures reflect the values of the societies that created them—whether as an act of devotion, a symbol of power, or a memorial to love.

Monuments as Universal Symbols: Connecting Humanity Across Time and Space

Monuments are universal symbols, representing shared human experiences such as devotion, love, and the quest for meaning. Structures like the Duomo in Florence or the Great Mosque of Djenné in Mali stand as towering expressions of religious faith. The Sagrada Familia in Spain and the Taj Mahal in India are not just architectural wonders but also acts of devotion, representing humanity’s quest for spiritual connection with the divine.

Yet, the emotional and spiritual significance of these monuments goes beyond religious expression. Monuments like the Paris Opera House, the Alhambra in Spain, or even the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles reflect human aspirations—love, sacrifice, patriotism, and intellectual curiosity. Each building embodies deep emotional resonance, whether it be the Taj Mahal’s eternal love or the Arc de Triomphe’s reflection of national pride.

This shared emotional connection to monumental architecture creates a thread that binds us across cultures and continents. Despite their cultural differences, these structures speak to universal human experience. Whether born out of a desire to honor a loved one or to express national identity, monuments serve as an emotional bridge between past and present, between individuals and their collective histories.

Cross-Cultural Influence: A Global Exchange of Ideas

The influence of one culture’s architectural style on another is not a new concept. In many ways, monumental structures are the result of a long history of cross-cultural exchanges.

Colonialism, though often obscured in contemporary narratives, played a significant role in this exchange of architectural knowledge. Western societies imposed their architectural ideals on their colonies, but they also borrowed elements from the regions they occupied. The Mughal empire, for example, influenced the design of many colonial structures in India, and today, that fusion of styles can still be seen in the architecture of cities like Kolkata and Mumbai.

Romanesque and Gothic architecture spread throughout Europe, leaving their mark on structures like the Duomo in Florence and Westminster Abbey in England. The Renaissance period was heavily influenced by Islamic art and architecture, with geometric patterns and ornamental designs permeating European structures. In more recent years, modern Western architecture has drawn inspiration from Eastern architectural principles, evident in the sleek design of skyscrapers and the incorporation of natural elements in urban landscapes.

This cross-cultural influence can be seen in the evolution of architectural styles, where elements from various cultures have been blended to create contemporary designs. The University of Deusto in Bilbao, Spain, reflects a modern synthesis of both traditional and contemporary styles, bridging the gap between history and the future.

In modern times, global trends like Art Deco and Brutalism have also created shared aesthetic values, seen in buildings like the Empire State Building in New York or the Chandigarh Capitol Complex in India. The global spread of these architectural styles highlights how interconnected the world has become, where design concepts transcend borders and reflect a collective vision of the future.

Monumental Missteps: How Periodization Distorts the Global Exchange of Architectural Ideas

However, the way we categorize and understand these architectural exchanges is heavily influenced by the concept of periodization—the historical process of dividing history into distinct periods. While periodization can offer a useful framework for studying history, it also creates hierarchical structures that shape how we view different cultures and their contributions to the world. In the context of architecture, periodization often reinforces the notion that Western art and architecture progress in a linear fashion, while other cultures and their monumental achievements are relegated to being merely contemporaneous or existing « around » Western history.

As Eric Hayot argues in his work « Against Periodization, » periodization is far from neutral. By dividing history into rigid timeframes, we inadvertently elevate certain cultural narratives (often Western) while marginalizing others. This approach not only simplifies the complexities of cultural exchange but also perpetuates stereotypes that reinforce biases. When we separate monuments and architectural styles by time and geography, we risk undermining the interconnectedness of global architectural history, which has been influenced by shared ideas and practices across cultures.

This hierarchical view is problematic because it overlooks how the exchange of architectural knowledge transcends temporal boundaries. It downplays the role of colonialism in the flow of ideas between the West and the rest of the world, as well as the influence of non-Western architectural styles on modern Western design. For example, the geometric patterns in Islamic architecture during the Renaissance had a profound influence on Western design, yet this exchange is often ignored or understated in favor of a narrative that positions Western architecture as « progressive » while other architectural traditions remain static.

Conclusion: Reflecting on the Shared Human Experience

Monuments are not just buildings; they are symbols of our collective human values—devotion, beauty, love, and the pursuit of knowledge. Across continents and centuries, these structures embody the universal desire to express emotion, beliefs, and aspirations through architecture.

Monuments continue to serve as cultural storytellers. They reflect the values of the societies that created them, offering glimpses into their religious, emotional, and political beliefs. The detailed carvings of the Taj Mahal, the grandeur of the Colosseum, and the spiritual weight of the Sistine Chapel all speak to the civilizations that built them, offering insights into their values, struggles, and triumphs.

As we reflect on these monumental structures, we are reminded of the shared human experience they represent. These buildings transcend time and space, linking us across centuries and continents, reminding us that despite our differences, we are bound by the same universal emotions—love, devotion, pride, and the desire to create something lasting. The beauty of these monuments lies not just in their physical form, but in their ability to connect humanity across borders, cultures, and time periods.

As we look to the future, it’s fascinating to consider what new monuments will be created to honor cultures and histories. How will future generations continue to build on this shared legacy of human creativity? An enduring legacy of human creativity that will continue to inspire, connect, and transcend.

Nida Kamal