French version below

January 2015. My family has a very specific ritual: every Saturday night, we used to watch a film or series. My parents suggested that my brother and I discover Twin Peaks. A simple pitch: Laura Palmer, a well-liked teenager, is found lifeless by the lake in Twin Peaks, a quiet town that hides many secrets. Little did I know at the time that this series would leave a deep impression on me.

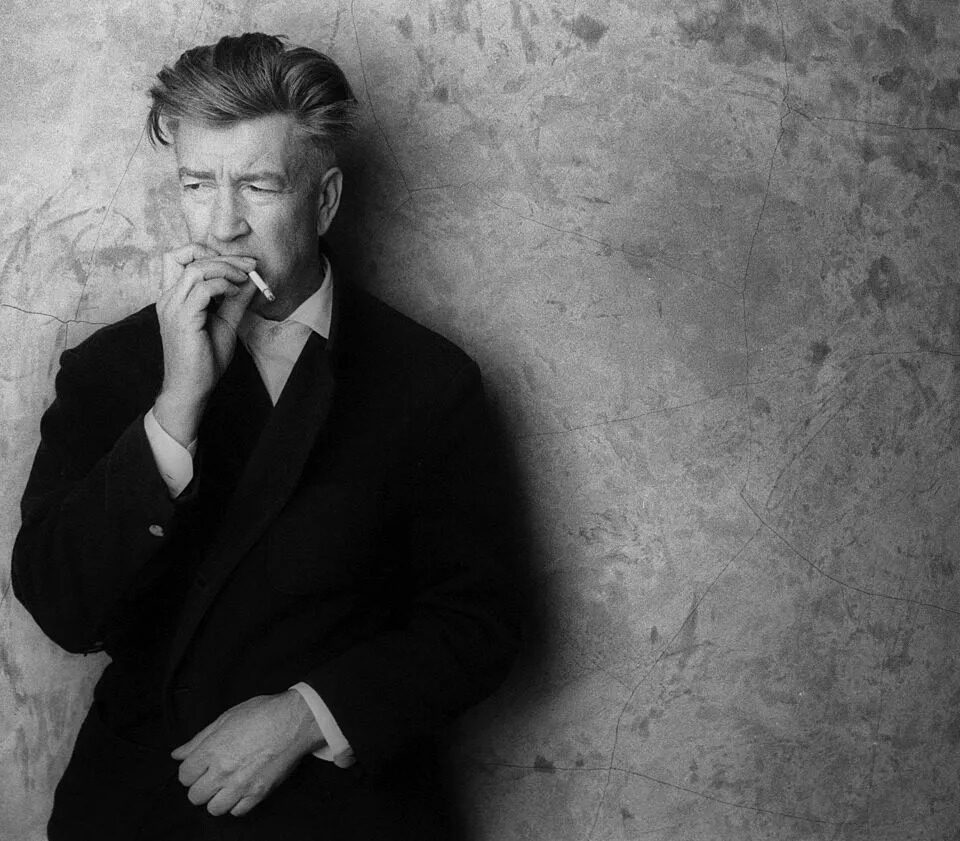

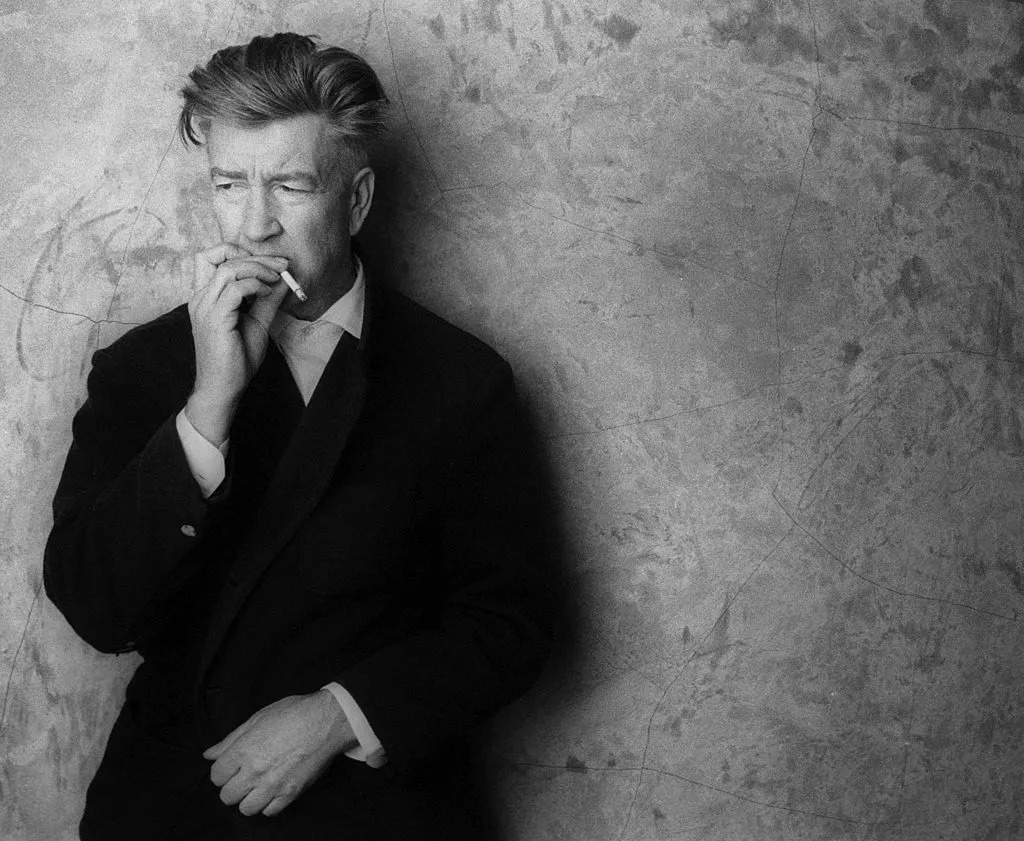

Ten years later, I enjoyed this cult series for a second time… only to learn in the following weeks that David Lynch had died. The news sounds a heartbreak for me. At the age of 78, he leaves behind a multitude of unanswered questions and a legacy that will remain forever elusive. His entire body of work is an enigma, still the subject of eternal theories and speculation.

David Lynch was not initially destined to become a film director. He entered the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts with the firm intention of becoming a painter. Deeply inspired by the work of Francis Bacon, Lynch was already projecting onto his paintings the dark, anxiety-inducing world that would later appear in his films. At the end of the 1960s, he began making animated short films, which were gradually mixed with live action. His many experiments culminated in Eraserhead (1977), a nightmarish first feature in which he brought his darkest fears to life.

His second film, Elephant Man (1980), is just as tragic, drawing heavily on the life of Joseph Merrick, a man with a deformed face. Nominated in eight categories at the Oscars, it marked the director’s public consecration. On the road to success, David Lynch was entrusted with the big-screen adaptation of Dune (1984), but his artistic demands diverged from commercial expectations. The film was cut by an hour, and received a great reception from both press and audience.

Blue Velvet (1986) was Lynch’s revenge, since he had control over the entire project right up to the final cut. The film divided critics as much for its unhealthy, revolting eroticism as for its strangely surreal nature. In 1990, while his fifth feature Wild at Heart was winning the Palme d’Or at the 43rd Cannes Film Festival, the pilot for Twin Peaks was broadcast on ABC. Without knowing it, David Lynch was to revolutionize the universe of series by combining his cinematic vision with the TV format. The first episode was a huge hit with American households and worldwide. The series became a must-see, remained enigmatic, and the answers were not to be found either in the prequel Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, released the following year, or in the third season, Twin Peaks: The Return, released in 2017.

Lynch followed this up with Lost Highway (1997), The Straight Story (1999) and Mulholland Drive (2001), other projects with powerful symbolism, and the last one Inland Empire (2006), a return to his freer, more spontaneous beginnings. In it, he explores the dark side of Hollywood, portraying disembodied characters trapped in a merciless industry.

If I had to sum up his cinema in a single word, “hors-norme” (literally out of the ordinary) would undoubtedly be the truest to his universe. David Lynch has never stopped thinking outside the box, playing with the rules of conventional narrative. The fact that his whole artwork so difficult to get is no accident. It is up to the viewer to put the pieces together and make their own interpretation. Like the Arte documentary David Lynch, une énigme à Hollywood (currently available), I would like to end this article with these words from David Lynch: “There is still so much to say, so many stories to tell. In the end, every life is a mystery until we find the key. We’re all heading in that direction, consciously or unconsciously.”

Marie Damongeot

David Lynch, la disparition du maître du cinéma d’art

Janvier 2015. Ma famille a un rituel bien précis : chaque samedi soir, nous regardons un film ou une série. Mes parents proposent à mon frère et moi de découvrir alors Twin Peaks. Le pitch : Laura Palmer, une adolescente appréciée de tous, est retrouvée sans vie au bord du lac de Twin Peaks, une ville tranquille qui cache bien des secrets. J’ignore à ce moment-là que cette série me marquera viscéralement.

Dix ans plus tard, je savoure une seconde fois cette série culte … avant d’apprendre dans les semaines suivantes que David Lynch est décédé. La nouvelle me fait l’effet d’un crève-cœur. A 78 ans, il laisse derrière lui une multitude de questions en suspens et un héritage à jamais insaississable. Son œuvre entière est une énigme qui fait encore aujourd’hui l’objet d’éternelles théories et spéculations.

David Lynch n’avait pourtant pas vocation à devenir réalisateur au départ. Il fait ses premiers pas à l’Académie des Beaux-Arts de Pennsylvannie avec la ferme intention de devenir artiste peintre. Profondément inspiré par l’œuvre de Francis Bacon, Lynch projette déjà sur ses tableaux un univers sombre et anxiogène que l’on retrouvera plus tard dans ses films. A la fin des années 1960, il entreprend de réaliser des court-métrages animés, puis progressivement mélés à des prises de vue réelles. Ses nombreuses expérimentations aboutissent à Eraserhead (1977), un premier-long métrage cauchemardesque dans lequel il donne vie à ses angoisses les plus noires.

Son second film, Elephant Man (1980), est d’un registre tout aussi tragique, puisqu’il s’inspire largement de la vie de Joseph Merrick, un homme au visage difforme. Nommé dans huit catégories aux Oscars, il sonne la consécration publique du réalisateur. Engagé sur la voie du succès, David Lynch se voit confier l’adaption sur grand écran de Dune (1984), mais ses exigences artistiques divergent des attentes commerciales. Le film est amputé d’une heure et reçoit un accueil mitigé de la presse et des spectateurs.

Blue Velvet (1986) apparaît alors comme la revanche de Lynch, qui a la main mise sur l’entièreté du projet jusqu’au final cut. Le film divise la critique autant par son érotisme malsain et révoltant que sa nature étrangement surréaliste. En 1990, tandis que la Palme d’Or du 43ème festival de Cannes est décernée à son cinquième long-métrage Sailor et Lula, le pilote de Twin Peaks est diffusé sur la chaîne ABC. Sans le savoir, David Lynch va révolutionner le monde des séries en conjuguant son regard de cinéaste au format TV. Le premier épisode rencontre un franc succès auprès des foyers américains et au-delà des frontières. Une série devenue incontournable qui restera néanmoins énigmatique, et dont on ne trouvera les réponses ni dans son prequel Twin Peaks : Fire Walk With Me sorti l’année suivante, ni dans sa troisième saison Twin Peaks : The Return sortie en 2017.

Lynch poursuit sa lancée avec Lost Highway (1997), Une Histoire Vraie (1999) et Mulholland Drive (2001), autres projets à la symbolique puissante, puis finalement Inland Empire (2006), qui s’annonce comme un retour à ses débuts plus libres et spontanés. Il y explore la part d’ombre d’Hollywood en mettant en scène des personnages désincarnés et pris au piège d’une industrie sans merci.

Si je devais résumer son cinéma, hors-norme serait sans doute le mot le plus fidèle à son univers. David Lynch n’a jamais cessé de sortir des sentiers battus en jouant avec les règles de la narration conventionnelle. Le fait que ses œuvres soient si difficilement déchiffrables n’a jamais été pensé au hasard. C’est au spectateur que revient la tâche (ou peut-être l’honneur ?) de rassembler les pièces du puzzle et de se faire sa propre interprétation. A l’instar du documentaire Arte David Lynch, une énigme à Hollywood (actuellement disponible), je terminerai cet article par ces paroles de David Lynch : « Il reste tant à dire, tant d’histoires à raconter. En fin de compte, chaque vie est un mystère jusqu’à ce que nous en trouvions la clé. On vogue tous vers cette direction, consciemment ou pas. »

Marie Damongeot