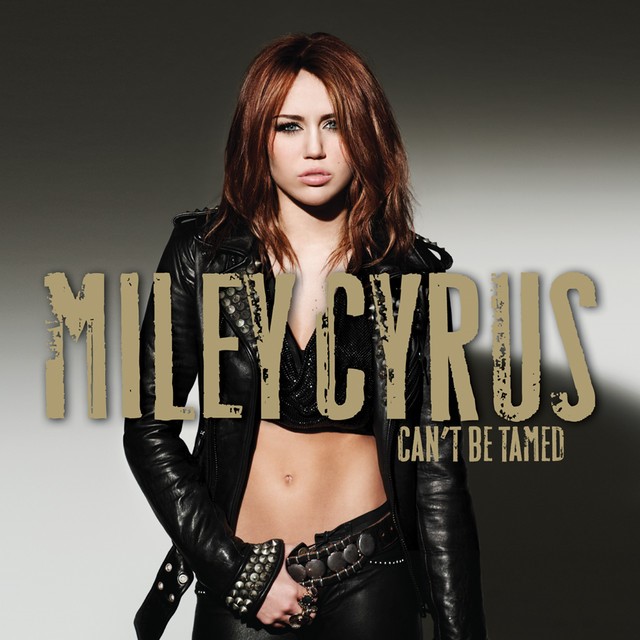

Miley Cyrus is my favorite singer; her work has always had a huge influence on my life. The image of a pop star is often discredited. In fact, I’m sure you couldn’t help but crack a smile when you read the title of my article. But a pop star can change lives, shape destinies, and make people dream!

Miley Cyrus changed my life when I was 9 years old. I was invited to the birthday party of my first and last girlfriend, Lisa. I was the only boy invited to her party. When it was time to open the gifts, Lisa unwrapped the Hannah Montana concert CD. A name I had never heard before, and one that immediately intrigued me. It wasn’t a name I was used to hear—unlike Sylvie, Corine, or Patricia—it was a star’s name! Lisa’s mom put the CD on the TV, and while Lisa and her friends, high on Coke and Smarties, went off to play, I stayed alone in the living room, mesmerized by this stunning singer, whose name hundreds of fans were chanting. The TV screen no longer existed—I was at the concert! I felt a deep, visceral connection to her! You might think I’m exaggerating, but it’s true! Miley Cyrus’ energy literally radiated through me!

After that birthday party, she became my obsession. Deep down, I was just like her—I lived in the countryside among cows, I sang (screamed) in my room, waiting for a talented agent to discover me and take me to Hollywood, where I would have a mansion and my star on the Walk of Fame! Best of both worlds, like she said!

Well, a rich old talent agent never came to rescue me—and maybe that’s for the best—but my destiny had taken a new turn. I wouldn’t be a soccer star like all the other boys; I would be a pop star. While my brother took soccer lessons, I asked my parents to sign me up for music theory classes. It definitly wasn’t High School Musical—it took us an hour to read three lines of sheet music and spit into flutes. But still, I was a little star at the Christmas and end-of-year recitals. You could say it was the start of my career.

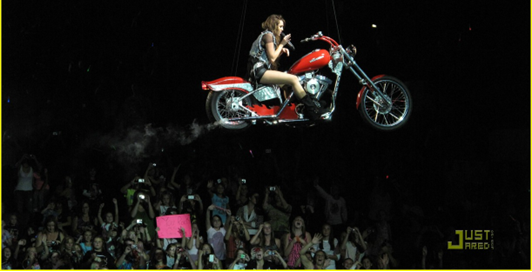

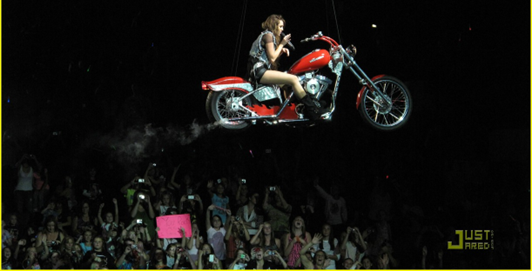

My mom noticed my interest in Miley Cyrus and, like any mother who discovers their child’s passion, she saw it as a bargaining tool! If I behaved well, she would take me to see Miley Cyrus in concert. Let me tell you—I behaved! I got excellent grades in school, and my mom kept her promise. We went to see Miley Cyrus in London. One of the most beautiful moments I shared with my mom. It’s a memory that is very dear to us (wipes tear). The highlight of the show was Miley Cyrus’ performance of I Love Rock ‘N Roll, where she flew over us on a motorcycle (super cool, I know). She then sang Party In the USA, and suddenly, I dreamed of hopping off a plane at LAX!

At the end of high school, I was lost—I didn’t know what to do. Well, actually, I did—I wanted to Party in the USA! I took the entrance exams for various Sciences Po schools because they offered exchange programs in the United States. I didn’t get in, so I enrolled in a preparatory class, thinking I could go on exchange through a business school. I was very lucky and got into Audencia, which had an exchange program in Fullerton, California. Time to Party in the USA!

I was living with other Audencia students who were also Miley fans. Like me, they had the « Miley Vision, » if I may say so—they didn’t see California as the land of crackheads, highways, cars, concrete, guns, and junk food. They saw California as the land of pool parties, beach sunsets, fame, mischief, and fun. We were there to have fun, Miley-style!

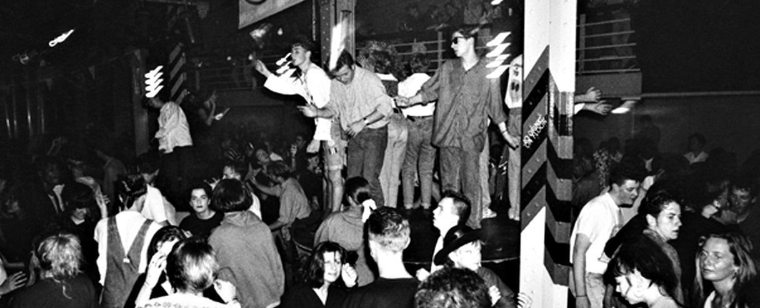

I had my Party in the USA when my buddy took my roommates and me to a nightclub in Anaheim. We blasted Party in the USA in the car, singing our hearts out, while watching the fireworks from Disney California Adventure Park through the sunroof. That was a full-circle moment!

So, I hope this article has inspired you to proudly declare your love for the pop star who holds a special place in your heart—because I’m sure you, too, have experienced incredible moments listening to Beyoncé, Rihanna, Katy Perry, or Shy’m. As for me, I’ll leave you now—I have my World Concert Tour to perform… in my bathroom.

J’adore Miley Cyrus !

Miley Cyrus est ma chanteuse préférée, son travail a toujours fortement influencé ma vie. La figure de la popstar est souvent décrédibilisée, d’ailleurs je suis sûr que vous n’avez pas pu vous empêcher d’esquisser un sourire en lisant le titre de mon article. Pourtant, une popstar ça change des vies, ça façonne des destinés et ça fait rêver !

Miley Cyrus a changé ma vie quand j’avais 9 ans. J’étais invité à l’anniversaire de ma première et dernière petite copine, Lisa. J’étais le seul garçon invité à sa fête. Au moment de l’ouverture des cadeaux, Lisa déballe le CD concert d’« Hannah Montana ». Un nom qui m’était inconnu et qui m’a tout de suite intrigué. Ce n’était pas un nom que j’avais l’habitude d’entendre, pas comme Sylvie, Corine ou Patricia, c’était un nom de star ! La mère de Lisa lance le CD à la télé, bourrées de Coca et de Smarties, Lisa et ses copines vont jouer pendant que je reste seul dans le salon, obnubilé par cette chanteuse magnifique dont des centaines de fans scandent le nom. L’écran de la télévision n’existait plus ! J’étais au concert ! Je me sentais viscéralement connecté à elle ! Vous allez vous dire que j’exagère, mais c’est vrai ! L’énergie de Miley Cyrus m’a littéralement irradiée ! Après ce goûter d’anniversaire elle est devenue mon obsession. J’étais comme elle dans le fond, je vivais à la campagne au milieu des vaches, je chantais (braillais) dans ma chambre en attendant qu’un agent de casting me découvre et m’emmène à Hollywood où j’aurais une villa et mon étoile au walk of fame ! Best of both worlds like she said !

Bon un vieux monsieur riche agent de casting n’est jamais venu me secourir et c’est peut-être mieux ainsi, mais mon destin avait définitivement pris une nouvelle tournure. Je ne serais pas une star du foot comme tous les autres garçons, je serais une popstar. Pendant que mon frère prenait des cours de foot, j’ai demandé à mes parents de m’inscrire à des cours de solfège. Alors ce n’était certainement pas High School Musical, on prenait une heure à lire trois lignes de partition et à cracher dans des flûtes. Mais quand même, j’étais moi aussi une petite star aux représentations des vacances de Noël et de fin d’année. Le début de ma carrière on peut dire. Ma mère avait senti mon intérêt pour Miley Cyrus et, comme toute mère qui découvre que son enfant a une passion, elle y a vu une monnaie d’échange ! Si je me comportais bien elle m’amènerait voir Miley Cyrus en concert. Je peux vous dire que je me suis tenu à carreau ! J’ai eu d’excellentes notes à l’école et ma mère a tenu sa promesse. Nous sommes allés voir Miley Cyrus à Londres. L’un des plus beaux moments que j’ai partagé avec ma mère. C’est un souvenir qui nous est très cher (petite larme). Le clou du spectacle a été l’interprétation de « I Love Rock’N Roll » par Miley Cyrus, qui est passé au-dessus de nous à moto (la classe je sais). Elle a ensuite chanté « Party In the USA » et soudain, j’ai rêvé to hop off a plane at LAX !

À la fin du lycée j’étais perdu je ne savais pas quoi faire. Enfin si, je voulais « Party In the USA » ! J’ai passé les concours des différents Science-Po car ils proposaient des échanges aux États-Unis. Je n’ai pas été reçu, je me suis alors orienté vers une classe préparatoire en me disant que je pourrais partir en échange avec une école de commerce. J’ai eu beaucoup de chance et j’ai obtenu Audencia qui proposait un échange en Californie à Fullerton. Time to « Party In the USA » ! J’étais en collocation avec d’autres étudiants d’Audencia qui eux aussi étaient des fans de Miley. Ils avaient comme moi la « Miley Vision », si je puis dire, ils ne voyaient pas la Californie comme le pays des crackheads, des autoroutes, des voitures, du béton, des armes à feu et de la mal bouffe. Ils voyaient la Californie comme le pays des pools party, des couchés de soleil à la plage, de la fame, des bêtises et du fun. On était là pour s’amuser à la manière de Miley ! J’ai eu my « Party In the USA » quand mon buddy nous a amené, mes collocataires et moi, en boîte de nuit à Anaheim. Nous avions mis « Party In the USA » à fond dans la voiture, nous chantions et regardions depuis le toit ouvrant le feu d’artifices tiré depuis Disney California Adventure Park. That was a full circle moment !

So, j’espère au travers cet article vous avoir donné envie de clamer haut et fort votre amour pour la popstar qui est chère à votre cœur, car je suis sûre que vous aussi vous avez vécu des moments incroyables en écoutant Beyoncé, Rihanna, Katy Perry ou Shy’m. Quant à moi je vous laisse, j’ai mon World Concert Tour à perform dans ma salle de bain.