With his antisemitic, misogynistic, and racist remarks, the iconic 47-year-old American artist Kanye West once again raises the eternal question: Should we separate the man from the artist? A question that may seem obvious to some, absurd to others, but nonetheless legitimate given the omnipresence of artists in our daily lives. Our museums, schoolbooks, television, and audio programs pay tribute to artists like Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Baudelaire, Woody Allen, Dr. Dre, or Michael Jackson. Students learn about the Dreyfus Affair through the film An Officer and a Spy directed by Roman Polanski. From a young age, we are thus taught to distinguish the man from the artist. This conditioning makes it all the more difficult to boycott—even figures as controversial as Kanye West. In this article, we will briefly revisit his artistic career, explore his many controversies, and attempt to understand why it is so difficult—for both the industry and fans—to break ties with an idol, or even a symbol.

A Look Back at Kanye West’s Artistic Career

Kanye West was born in 1977 in Atlanta into a middle-class family. His mother, was an English professor. Kanye first gained attention as a producer for small labels. His ability to transform “samples” into true sonic works of art revolutionized hip-hop production and quickly earned him recognition in the music industry. He later worked with major artists such as Jay-Z in 2001 and Alicia Keys in 2003. His innovative approach set him apart—blending soul, gospel, and contemporary rhythms, he established a unique musical identity that would later become the hallmark of his own albums.

Kanye’s shift to becoming a solo rapper—his childhood dream—marked a turning point in his career. The 2004 album The College Dropout was a true manifesto of his ideas. It broke conventions by offering socially conscious lyrics (particularly on racism) at a time when popular rap was dominated by “gangsta” tropes à la 2Pac or Dr. Dre—flashy cars, gold chains, and women objectified as background props. Kanye’s more minimalist and artistically refined visuals and musical style disrupted the industry.

Beyond music, Kanye also made a significant impact on fashion and culture. His collaborations with luxury brands and his own collections showcase his ability to influence far beyond musical boundaries, establishing him as a true trendsetter.

For more insight into his artistic journey, I highly recommend Seb la Frite’s documentary On Youtube, which thoroughly explores Kanye’s career (although it focuses less on the recent controversies).

Thus, Kanye West’s musical legacy is immense. His innovation and ability to reinvent himself throughout his career have influenced generations of artists and helped shape cultural landscapes, with countless fans supporting every one of his ventures. Yet, despite his artistic genius and contributions to the industry, he has also shocked, offended, insulted, and crossed lines that few would have imagined. So how have fans and the industry reacted to his many controversies? Has the public managed to boycott the rapper? Is it even their responsibility? Before we answer these questions, let’s go over his most significant controversies in recent years.

His Major Controversies

Interrupting Taylor Swift at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards

In 2009, Kanye made headlines by interrupting Taylor Swift during her acceptance speech for Best Female Video at the MTV Video Music Awards. He stormed the stage and declared that Beyoncé deserved the award instead. This incident was the first in a long series and led to a wave of criticism from both media and the public. A behavior I find deeply misogynistic—relying on supposed male superiority, Kanye deemed himself entitled to decide which woman deserved the award…

Antisemitic Remarks in Interviews

During multiple interviews, Kanye West made antisemitic comments based on charts and “data” whose sources remain unverified. He openly claimed that Jewish people control the media and influence the music industry. On Alex Jones’ show Infowars, he went so far as to praise Adolf Hitler: “I see good things about Hitler… Every human being has something of value they brought to the table, especially Hitler.”

Racist and Controversial Comments About Slavery

In 2018, Kanye caused major backlash by stating in a televised interview that slavery “was a choice.” Additionally, many have seen the viral videos on TikTok or Instagram showing him at the 2022 Paris Fashion Week wearing a T-shirt that said “White Lives Matter.”

Pushing Boundaries Further: Tweets and Nazi Merchandise.

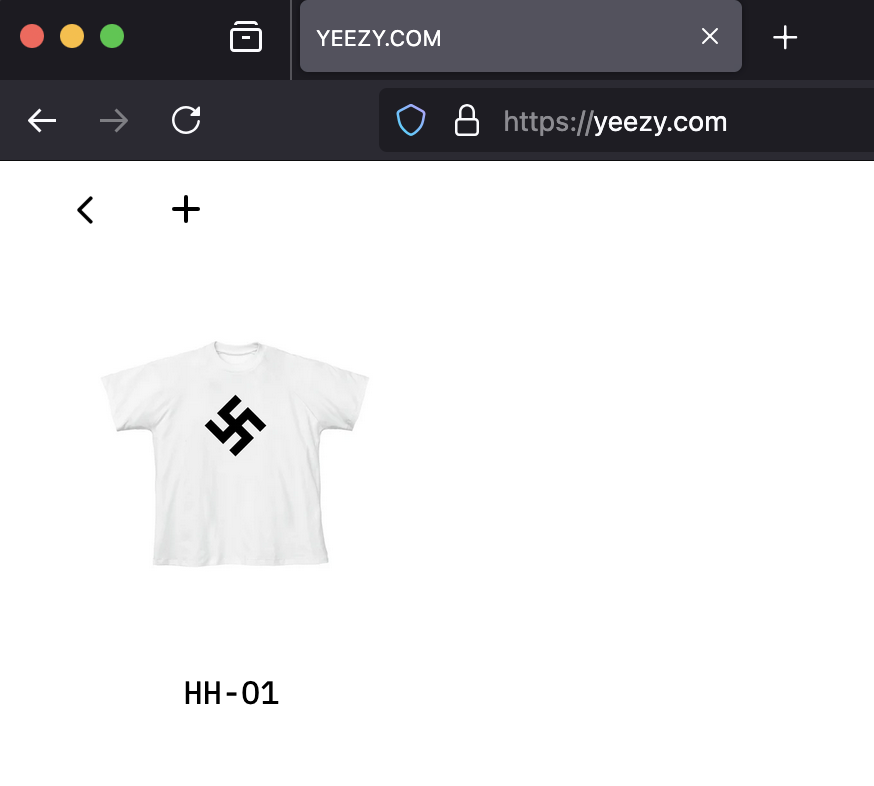

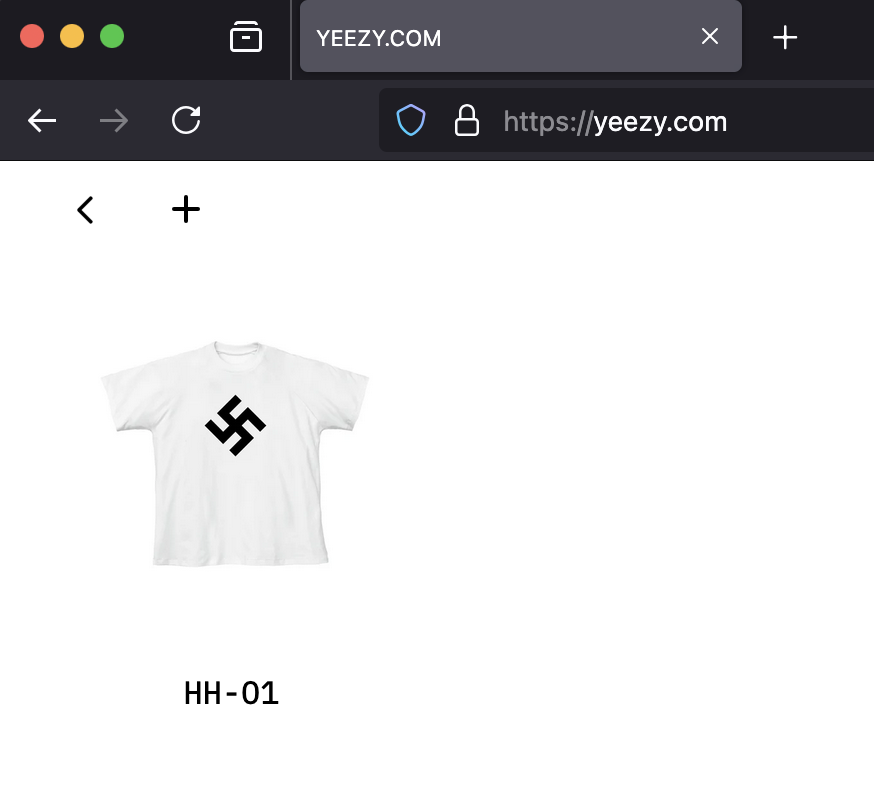

In February 2025, the 47-year-old rapper ramped up his antisemitic, racist, and misogynistic rhetoric with tweets like: “I love Hitler, now what bitches,” “I am a Nazi,” and “Call me Yaydolf Yitler.” He also (unsurprisingly) retweeted Elon Musk’s Nazi salute during Donald Trump’s inauguration. That same month, Kanye bought a Super Bowl halftime ad. It featured him lying in a dentist’s chair filming himself with his phone. He said he spent all his money on the ad and urged viewers to visit “Yeezy.com.” Initially, it looked like a regular fashion site—until it went blank, leaving only one item for sale: a plain white T-shirt with a swastika, priced at $20.

This raises the question: How, despite these remarks, can he still receive such widespread media coverage? Why isn’t he boycotted by the companies enabling that exposure? How did he even secure a Super Bowl ad—one of the most viewed events in the world?

The Difficulty of Boycotting an Artist – Separating the Man from the Art

Kanye West’s controversies are not new—they’ve been happening since 2009. Yet, his shocking and harmful comments haven’t stopped his rap career or his growing influence, especially among younger audiences. While some brands like Adidas and Gap cut ties with him, others continue to collaborate. Many organizations still give Kanye platforms to amplify his voice. I wonder—how was he allowed to purchase a Super Bowl ad, an event watched by over 115 million people? And more worryingly, who’s behind that T-shirt? Clearly, Kanye didn’t do it all alone. This collaboration could stem from respect for his art—or, more disturbingly, from support or indifference toward his views.

This specific case highlights a flaw in the American system: a failure to regulate or punish individuals or organizations involved in discriminatory actions. We’ve seen this recently with Trump’s election, where the Nazi gestures by Elon Musk or Steve Bannon (Trump’s former advisor) went unpunished.

So what are the solutions? From a commercial standpoint, I believe the answer is clear: as Adidas and Gap did, companies should cut ties. For the public, boycotting is a personal choice—one that usually happens naturally once people are properly informed. This is why media and access to accurate information are so crucial.

Personally, I believe that constantly trying to separate art from the artist sometimes leads us to normalize the intolerable. Cultural impact should never be used as an excuse for irresponsibility. It’s time we collectively accept that talent should never be a free pass !

Fanny Annequin

Kanye West et l’éternel débat de séparer l’homme de l’artiste

Avec ses propos antisémites, misogynes et racistes, l’artiste emblématique américain de 47 ans, Kanye West, soulève une fois de plus l’éternelle question : Doit-on séparer l’homme de l’artiste ? Une question dont la réponse semble évidente pour certains, absurde pour d’autres, mais bien légitime à être poser compte tenu de l’omniprésence des artistes dans notre quotidien. Nos musées, livres scolaires, programmes télévisés et audios, rendent hommage à des artistes comme Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Baudelaire, Woody Allen, Dr.Dre ou Michael Jackson. On enseigne aux élèves l’affaire Dreyfus à travers le film « J’accuse » réalisé par Roman Polanski. Dès l’enfance, nous sommes ainsi éduqués et amenés à distinguer l’homme et l’artiste. Cette construction rend d’autant plus difficile le boycott, même face à des figures aussi controversées que Kanye West. Nous allons, au cours de cet article, revenir brièvement sur sa carrière en tant qu’artiste, ses nombreuses polémiques, et enfin nous tenterons d’expliquer pourquoi il est si difficile, pour l’industrie comme pour les fans, de rompre avec une idole, voire un symbole.

Retour sur la carrière artistique de Kanye West

Kayne West né en 1977 dans la ville d’Atlanta, dans une famille de la classe moyenne. Sa mère d’origine anglaise, est professeure d’anglais. Le jeune américain commence à faire parler de lui tout d’abord en tant que producteur pour des petits labels. Sa capacité à transformer des « samples » en véritables œuvres d’art sonore a révolutionné la production hip-hop et a très vite fait connaître l’artiste dans l’industrie de la musique. Il a ensuite travaillé avec de grands artistes comme Jay-Z en 2001 ou Alicia Keys en 2003. Il se différencie grâce à une approche musicale très innovante. En effet, mêlant soul, gospel et rythme contemporains, il a permis d’imprimer une identité musicale unique qui va plus tard devenir la marque de fabrique de ses propres albums. Le passage de Kanye en tant que rappeur solo (ce qu’il rêve depuis tout petit) marque un tournant décisif dans sa carrière. C’est l’album The College Dropout sorti en 2004, qui est un véritable manifeste de ses idées. Cet album a bousculé les conventions en proposant des textes socialement engagés (notamment sur la cause du racisme) et loin des stéréotypes de l’époque où le rap qui faisait des « streams » était un rap « brut », « gangsta », à la 2Pac ou Dr Dre, un rap très ostentatoire : illustré par des grosses voitures, des grosses chaînes en or et où les femmes, en arrière-plan, ne servaient que de « décor ». Ainsi, les clips et le style musical de Kanye, plus minimalistes et artistiquement recherchés, viennent bousculer l’industrie.

De plus, l’artiste ne s’est pas limité à la musique, il a aussi eu un véritable impact sur la mode et la culture. Sa collaboration avec des marques de luxe et le lancement de ses propres collections témoignent de sa capacité à influencer bien au-delà des frontières musicales, faisant de lui un véritable « trendsetter ».

Pour plus d’information sur son parcours de vie artistique, je vous vraiment conseille le documentaire de Seb la Frite, qui revient en détail sur toute l’histoire du rappeur (moins sur ses polémiques qui ont pris un tournent dernièrement).

Ainsi, l’héritage musical de Kanye West est immense. Son esprit d’innovation et sa capacité à se réinventer tout au long de sa carrière a influencé des générations d’artistes et a façonné le paysage culturel avec de nombreux fans qui le supportent et soutiennent dans chacun de ses projets. Pourtant, malgré son génie artistique et ce que l’artiste a apporté à l’industrie, il a aussi choqué, offensé, injurié et dépassé bien des limites que peu n’auraient pu imaginer. Alors, comment les fans et l’industrie ont-t-ils réagit face à ces différentes controverses ? Le public a-t-il réussit à boycotter le rappeur ? Est-ce même son devoir ? Avant de répondre à toutes ces questions, revenons sur ses principales polémiques qui ont marquées les dernières années.

Ses différentes polémiques

L’Interruption de Taylor Swift aux MTV Video Music Awards en 2009

En 2009, lors de la cérémonie des MTV Video Music Awards en 2009, Kanye West a marqué les esprits en interrompant le discours de Taylor Swift, alors qu’elle venait de remporter le prix de la meilleure vidéo féminine. Il est monté brusquement sur scène pour affirmer que Beyoncé méritait le prix à la place de la chanteuse. Cet évènement a été le premier d’une longue série et a entrainé une vague de critiques, tant de la part des médias que du public. Un comportement que je considère très misogyne car jouant de sa prétendue supériorité masculine, Kayne se considère légitime d’affirmer de façon certaine, qui des femmes, méritaient le plus le prix de la meilleure vidéo féminine…

Des propos antisémites lors d’interviews

Lors d’interviews devant des journalistes, Kayne West a, à plusieurs reprises, tenu des propos antisémites basés sur des « données », graphiques, dont les sources restent à vérifier… Il explique ouvertement que les juifs contrôlent les médias et influencent le secteur de la musique. Dans l’émission « Infowars » d’Alex Jones, il n’a carrément pas hésité à faire l’éloge d’Adolf Hitler : « Je vois de bonnes choses chez Hitler… Chaque être humain a quelque chose de valeur qu’il a apporté, en particulier Hitler. »…

Des propos racistes et controversés sur l’esclavage

En 2018, Kanye West a déclenché une controverse majeure en affirmant lors d’une interview télévisée, que l’esclavage « était un choix ». Par ailleurs, beaucoup ont dû voir passer des vidéos sur TikTok ou Instagram où nous voyons l’artiste lors de la Fashion Week de Paris de 2022, porter un Tee-Shirt sur lequel était écrit « White Lives Matter ».

Toujours plus loin…, les tweets, T-Shirt Nazi en vente sur son site

En février 2025, le rappeur de 47 ans a multiplié les tweets antisémites, racistes et misogynes. « I love Hitler, now what bitches », « I am a nazi », « Call me Yaydolf Yitler ». Il a aussi (sans surprise) retweeté le salut nazi effectué par Elon Musk lors l’investiture de Donald Trump. En février 2025, le rappeur s’est acheté un spot publicitaire lors de la mi-temps du Superbowl. Nous le voyons allongé sur un siège de dentiste se filmant avec son smartphone. Il explique avoir dépensé tout son argent pour cette pub et termine son spot en invitant les gens à aller sur un site : « Yeezy.com ». Au départ, les gens tombent sur un site commercial qui vend ses articles mode, mais rapidement…page blanche. Tous les articles en vente ont disparu sauf un t-shirt blanc avec d’une croix gammée à 20$.

Une question se pose alors, comment, malgré ses propos, l’artiste peut-il encore avoir autant de diffusion médiatique ? Pourquoi n’est-il pas boycotté par les entreprises en charge de cette diffusion ? Comment a-t-il pu arriver à avoir ce spot publicitaire lors d’un des évènements les plus visualisés au monde de l’année ?

La difficulté de l’industrie et du public à boycotter un artiste – à séparer l’homme de l’artiste

Les polémiques autour de Kanye West ne datent pas du mois passé. En effet, depuis 2009, l’artiste tient des propos choquants et graves qui ne lui ont pas empêché de continuer sa carrière en tant que rappeur et d’augmenter son influence auprès de son public (majoritairement jeune). Si son comportement lui a fait perdre de gros contrats avec des marques telles que Adidas ou Gap, d’autres continuent de signer avec lui. De nombreuses organisations laissent à Kanye West la possibilité d’étendre son influence et de se faire entendre. Je me demande, comment a-t-il pu avoir la possibilité d’acheter un spot publicitaire lors du Super-Bowl ? Un évènement qui, pour rappel, est diffusé devant plus de 115 millions de téléspectateurs ! Une des questions des plus inquiétantes est, qui est derrière ce Tee-Shirt ? Car il est évidemment que d’autres parties ont été engagés sur le projet. Kanye West ne peut pas agir seul. L’explication de cette collaboration avec l’artiste peut venir d’un respect pour son art ou, plus tristement, d’un soutien ou d’une indifférence à ses propos. Cet exemple précis, illustre bien une des failles du système américain, qui ne contrôle pas, ne puni pas, les auteurs ou les organisations d’actes à caractère discriminants. Nous l’avons bien vu récemment avec l’élection de Trump, où le signe Nazi effectué par Elon Musk ou Steve Bannon (l’ancien conseillé de Donald Trump), n’ont pas été sanctionné par la loi. Quelles sont les solutions ? Personnellement, commercialement pour moi, il n’y a pas de débat, comme l’ont fait Addidas et Gap, il faut rompre les contrats. Concernant le public, le boycott est évidemment un choix personnel, qui se fera dans la majorité des cas naturellement une fois le public bien informé. D’où l’importance des médias et de bien s’informer…

Ainsi, à titre personnel je trouve qu’à force de vouloir séparer l’art de l’artiste, on finit parfois par normaliser l’intolérable. L’impact culturel ne peut pas servir d’excuse à l’irresponsabilité. Il est temps, collectivement, d’assumer que le talent ne doit jamais être un passe-droit !

Fanny Annequin